Quad9 DNS (9.9.9.9): how it works, benefits, alternatives

By CaptainDNS

Published on December 19, 2025

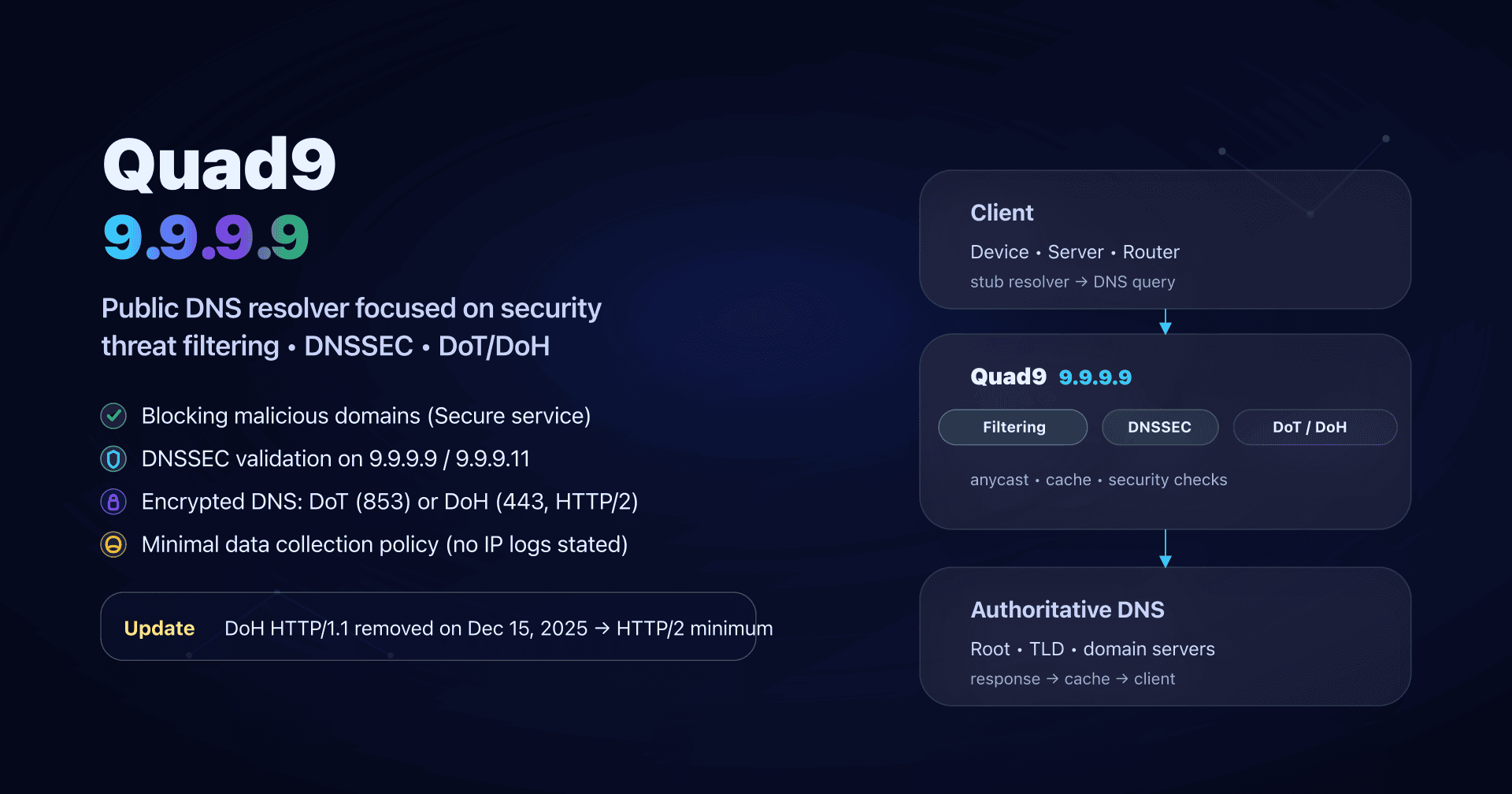

- 📢 Quad9 (9.9.9.9) is a public DNS resolver focused on security and privacy, easy to deploy for SMBs.

- Use 9.9.9.9 for the "Secure" service (malicious-domain blocking + DNSSEC); keep 9.9.9.10 only for debugging.

- To avoid snooping and DNS hijacks, prefer an encrypted transport (DoT or DoH) and verify the protocol actually used.

- Since December 15, 2025, Quad9 no longer supports DoH over HTTP/1.1: any DoH client must speak HTTP/2 (otherwise, switch to DoT).

Your "default" DNS (often your ISP's, or the one handed out via DHCP on the network) is rarely a deliberate choice. Yet the DNS resolver sees every domain name your machines try to reach and it can also influence security (blocking malicious domains) and availability (outages, latency, errors).

Quad9 is a popular alternative when you want a public DNS focused on security + privacy: it can block domains associated with malware/phishing and claims a minimal collection policy (notably no IP address logging on the DNS service). It's typically useful for sysadmins / DevOps / SMB CTOs who want a security gain "right now", without deploying a proxy or an agent on every machine.

We'll cover how Quad9 works, which addresses to use (9.9.9.9 / 9.9.9.10 / 9.9.9.11), how to configure it properly (router, endpoints, internal forwarder), how to test what's really happening… and the update to remember: the end of DoH over HTTP/1.1 since December 15, 2025.

Quad9 and 9.9.9.9 in two minutes

Quad9 is a public recursive DNS resolver (a DNS resolution service you can use instead of your ISP). It is mainly known for:

- Threat filtering: on the "Secure" service, Quad9 can refuse to resolve domains associated with malware, phishing, botnets, etc.

- DNSSEC validation (on "Secure" services): resolution fails if a signed DNS answer is tampered with.

- Privacy: Quad9 says it does not collect or log IP addresses on its DNS service, and limits collection to aggregated data.

- Encryption: you can use Quad9 in classic DNS (Do53) or encrypted DNS via DoT (DNS-over-TLS) and DoH (DNS-over-HTTPS), and also via DNSCrypt.

The best-known entry point is 9.9.9.9 (and its IPv4 "secondary" 149.112.112.112): that's the "Secure" service, generally the right default when you don't want to overthink it.

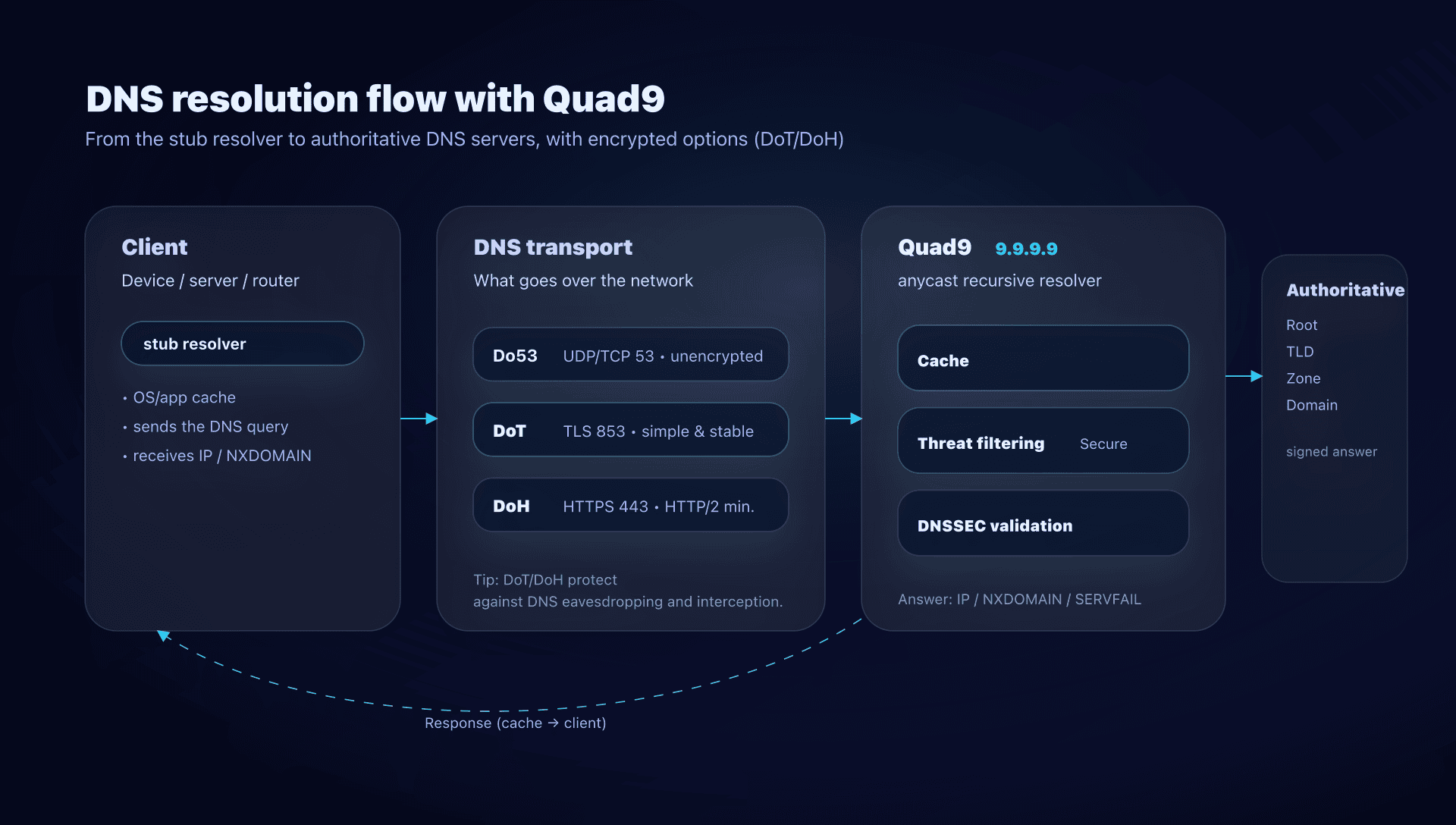

How does Quad9 resolve a domain name?

When a workstation tries to reach api.captaindns.com, it doesn't know the IP. So it asks DNS.

With Quad9, the path looks like this:

- The client sends a DNS query (via the OS, the router, a forwarder…).

- Quad9 receives the query and first checks its cache.

- If not cached, Quad9 performs recursive resolution (root → TLD → authoritative servers).

- On the "Secure" service, Quad9 also compares the domain against threat intelligence:

- if the domain is identified as malicious, Quad9 typically returns an NXDOMAIN (the domain "doesn't exist" from the client's perspective).

- If DNSSEC is involved and validation fails, the response can be a SERVFAIL (validation error).

What you see on the client side when it blocks

This matters in operations: a DNS block often looks like "the Internet is down".

- If Quad9 blocks a malicious domain: you get NXDOMAIN.

- If the domain truly doesn't exist: you also get NXDOMAIN.

- If DNSSEC fails: often SERVFAIL.

The practical trick: Quad9 provides ways to differentiate "NXDOMAIN because blocked" vs "NXDOMAIN because truly nonexistent" (we'll come back to it in the tests section).

Benefits and limits of Quad9

What Quad9 delivers right away

- Risk reduction "on click": some malicious domains no longer resolve.

- Fewer DNS leaks if you enable DoT/DoH: a public Wi‑Fi sees far less of what you resolve.

- DNSSEC already validated on Secure services: less risk of poisoning or tampered answers on signed zones.

- Lightweight deployment: a DNS change on the router or a local forwarder is often enough.

What Quad9 does not replace

- A web proxy or a SASE product: Quad9 operates at the DNS layer, not at URL, HTTP or TLS inspection.

- An adblocker: Quad9 is threat‑oriented, not ads/trackers (even if there can be overlap).

- A per‑user/endpoint policy: you don't get, natively, "Marketing vs Dev vs Guests" profiles like in managed DNS solutions geared toward enterprise.

The right framing: Quad9 is a baseline layer (often very cost‑effective), not a single shield.

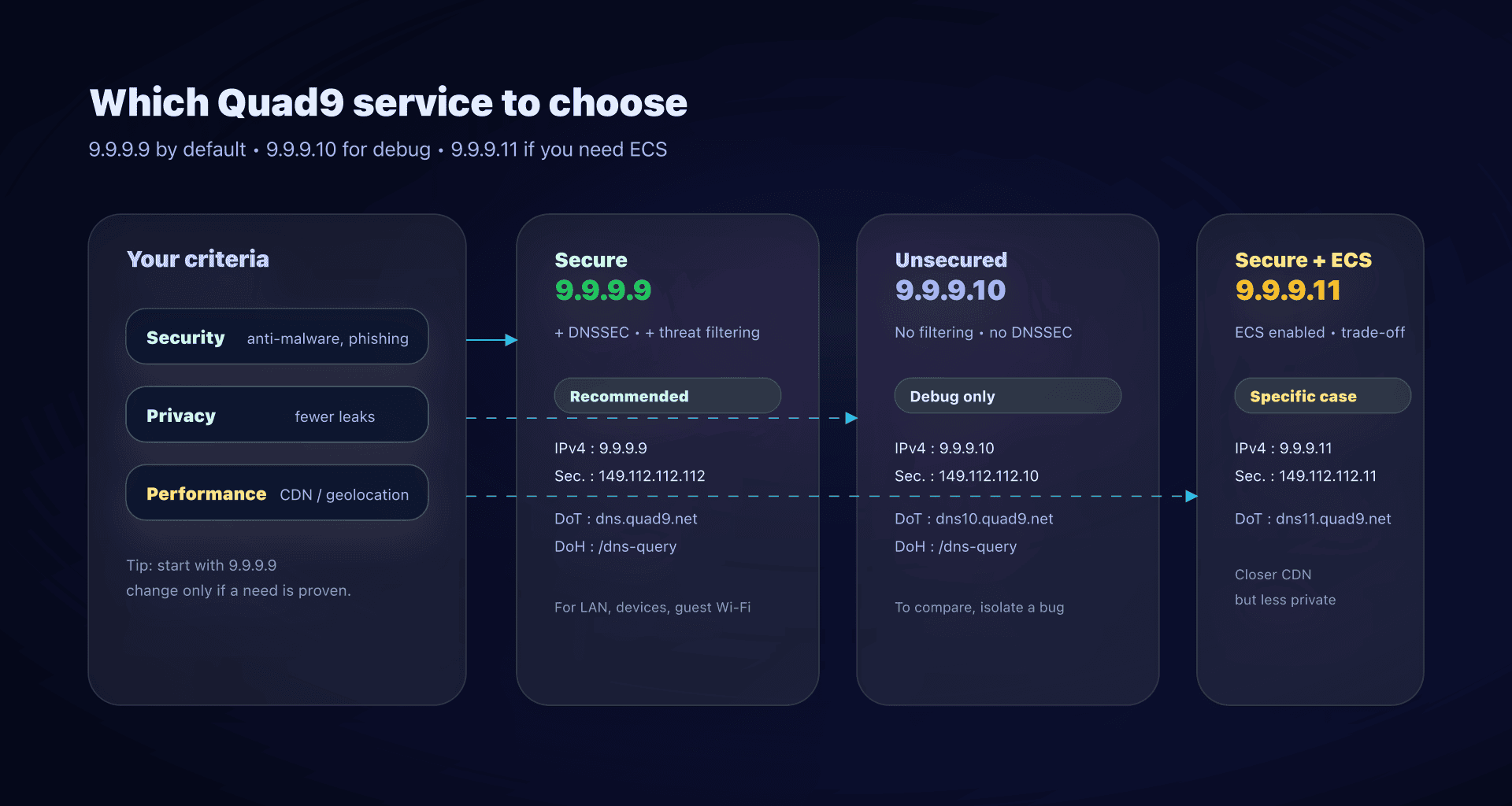

Quad9 services to know

Quad9 doesn't provide "one DNS", but several variants. In practice, you'll mostly run into these three:

| Service | Use when | Threat blocking | DNSSEC | ECS | IPv4 addresses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9.9.9.9 "Secure" | General case, SMBs, endpoints, guest Wi‑Fi | ✅ | ✅ | ❌ | 9.9.9.9, 149.112.112.112 |

| 9.9.9.10 "No Threat Blocking" | Debugging, comparisons, specific needs | ❌ | ❌ | ❌ | 9.9.9.10, 149.112.112.10 |

| 9.9.9.11 "Secure + ECS" | CDN geo/perf issues, unusual network cases | ✅ | ✅ | ✅ | 9.9.9.11, 149.112.112.11 |

Useful addresses and endpoints

Secure service (recommended):

IPv4 : 9.9.9.9, 149.112.112.112

IPv6 : 2620:fe::fe, 2620:fe::9

DoT : dns.quad9.net (port 853)

DoH : https://dns.quad9.net/dns-query

No Threat Blocking service:

IPv4 : 9.9.9.10, 149.112.112.10

IPv6 : 2620:fe::10, 2620:fe::fe:10

DoT : dns10.quad9.net (port 853)

DoH : https://dns10.quad9.net/dns-query

Secure + ECS service:

IPv4 : 9.9.9.11, 149.112.112.11

IPv6 : 2620:fe::11, 2620:fe::fe:11

DoT : dns11.quad9.net (port 853)

DoH : https://dns11.quad9.net/dns-query

Should you enable ECS

ECS (EDNS Client Subnet) sends partial location information (a slice of your IP prefix) to authoritative/CDN servers. Result: you can get a "better" CDN POP (lower latency) in some networks where anycast sends you to a Quad9 site that's not ideal for your actual geography.

The trade‑off:

- ✅ Potentially better CDN performance (video, large platforms).

- ❌ Less privacy, because part of your prefix is used for geolocation.

In practice: start with 9.9.9.9, switch to 9.9.9.11 only if you observe a real issue (abnormal latency to a service, wrong geolocation, etc.).

Do53, DoT, DoH and DNSCrypt

People often confuse "changing your DNS" with "encrypting your DNS". It's not the same.

Do53

Do53 is classic DNS: UDP/53 (and sometimes TCP/53). Easy and universal, but:

- visible (sniffable) on the network,

- redirectable (some networks intercept port 53),

- easier to manipulate for a local attacker (public Wi‑Fi, guest network…).

DoT

DoT (DNS‑over‑TLS) encrypts DNS at the transport level (TCP + TLS, usually port 853). Advantages:

- often available at the OS level (notably Android via "Private DNS", Linux via systemd‑resolved, etc.),

- easier to proxy in a router/forwarder,

- no HTTP wrapping: fewer surprises client‑side.

DoH

DoH (DNS‑over‑HTTPS) encapsulates DNS in HTTPS (port 443). It's handy in environments where 853 is filtered, but more "webby".

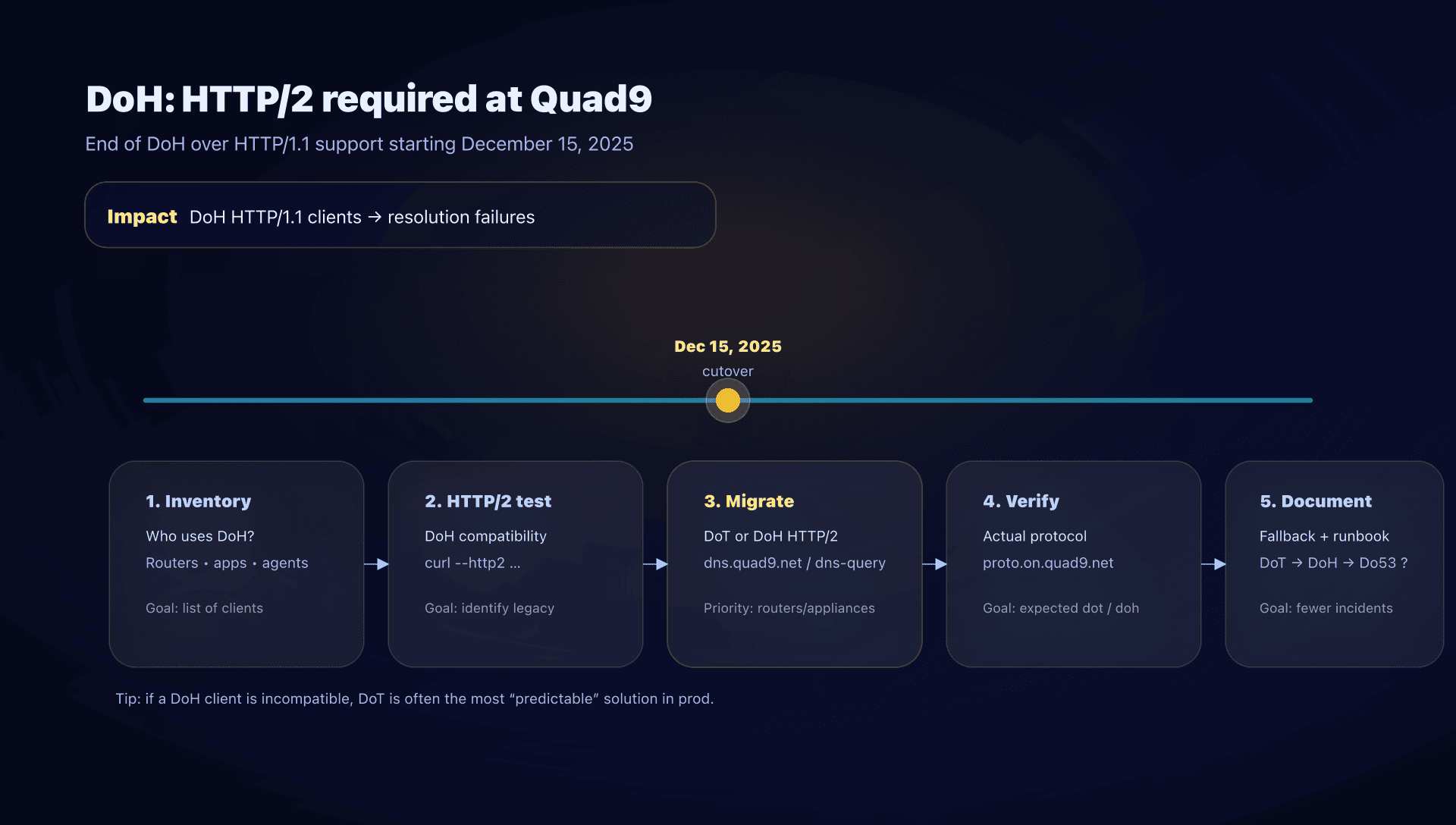

Important point for Quad9: DoH over HTTP/1.1 support was removed starting December 15, 2025. Concretely, a DoH client must be HTTP/2 compatible (or higher).

DNSCrypt

DNSCrypt is an alternative DNS encryption protocol, mostly present in certain clients/proxies (dnscrypt‑proxy, some appliances, etc.). You'll mostly use it if you already have DNSCrypt tooling or specific constraints.

DNS performance: how to get a sense without fooling yourself

"Which DNS is fastest?" is a tricky question, because:

- the cache (local + resolver) skews tests,

- performance depends on your network, anycast, and peering,

- some apps mostly feel first‑query latency, others benefit from cache.

A simple and honest method:

- Test several names (CDN, SaaS, internal domains).

- Repeat tests at different times.

- Compare Do53 and DoT/DoH if you plan to encrypt.

Quick example with dig (repeat on multiple domains):

dig @9.9.9.9 www.captaindns.com A +tries=1 +time=2

dig @149.112.112.112 www.captaindns.com A +tries=1 +time=2

If you have a local forwarder (Unbound/dnsdist), measure latency as seen by your endpoints, not just what the forwarder sees.

Configuring Quad9 in practice

Choose where to configure it

You have 3 possible layers, and they don't cover the same needs:

- At the router/DHCP level: simple, covers "almost everything", but often in Do53 (so unencrypted).

- At the endpoint/OS level: good for native DoT/DoH, useful on mobile laptops.

- Via a local forwarder (recommended for SMBs if you want encryption everywhere): endpoints talk to local DNS, and local DNS talks to Quad9 over DoT/DoH.

Option 1: Router and DHCP

Goal: all endpoints use Quad9 without touching each machine.

- Configure the LAN primary/secondary DNS to:

9.9.9.9and149.112.112.112- (and ideally the corresponding IPv6 if your LAN uses IPv6)

Keep in mind:

- An endpoint can "cheat" by setting a static DNS (or enabling DoH in the browser).

- On a "hostile" network (hotel, hotspot), port 53 can be intercepted.

Option 2: Linux endpoints and servers with systemd‑resolved

Simple DoT example (adapt to your distro):

# /etc/systemd/resolved.conf

[Resolve]

DNS=9.9.9.9 149.112.112.112

DNSOverTLS=yes

DNSSEC=no

Apply:

sudo systemctl restart systemd-resolved

resolvectl status

⚠️ Avoid enabling DNSSEC at the forwarder/OS "on top" if you already use an upstream that validates DNSSEC: you'll risk double validation, or even annoying behavior depending on the implementation.

Option 3: Enforce encryption via a local forwarder

This is the most robust strategy for enterprise networks: endpoints use your internal DNS, and your internal DNS encrypts to Quad9.

Example with Unbound (simplified):

# /etc/unbound/unbound.conf.d/quad9.conf

forward-zone:

name: "."

forward-tls-upstream: yes

forward-addr: 9.9.9.9@853#dns.quad9.net

forward-addr: 149.112.112.112@853#dns.quad9.net

This pattern brings several benefits:

- encryption outbound,

- local cache (faster answers),

- single control point (observability, troubleshooting).

Testing that you're using Quad9 and the right protocol

Test 1: Confirm you're using Quad9

Quad9 provides a control page: on.quad9.net. If that page doesn't indicate you're on Quad9, another DNS is being used (VPN, forced DNS, static DNS, etc.).

Test 2: Know if it's encrypted: Do53, DoT or DoH

Quad9 exposes a handy "TXT test".

On Linux/macOS:

dig +short txt proto.on.quad9.net.

On Windows PowerShell:

Resolve-DnsName -Type txt proto.on.quad9.net.

Possible answers (examples):

do53-udp/do53-tcp→ unencrypted DNSdot→ DNS‑over‑TLSdoh→ DNS‑over‑HTTPSdnscrypt-udp/dnscrypt-tcp→ DNSCrypt

If you get NXDOMAIN: your query didn't go to Quad9.

Test 3: Verify a Quad9 block

Quad9 uses a test domain: isitblocked.org.

dig @9.9.9.9 isitblocked.org | grep "status\|AUTHORITY"

- NXDOMAIN +

AUTHORITY: 0→ Quad9 block - NXDOMAIN +

AUTHORITY: 1→ truly nonexistent domain

Update: end of DoH over HTTP/1.1 since December 15, 2025

Key takeaway - ⚠️ Quad9 removed DNS‑over‑HTTPS over HTTP/1.1 starting December 15, 2025.

- If you use DoH, verify your clients speak HTTP/2 (most modern browsers already do).

- Known problematic devices: MikroTik RouterOS configured for DoH (DoH implementation without HTTP/2).

- If incompatible, the "no surprises" path is to switch to DoT (no HTTP layer).

How to quickly audit your DoH estate

- Inventory: who is doing DoH? (browsers, endpoint agents, routers, appliances, forwarders).

- HTTP/2 test on Quad9's DoH endpoint:

curl --http2 -I https://dns.quad9.net/dns-query - List legacy clients: typically network devices that adopted DoH early but without an HTTP/2 stack.

- Decide the fallback (document it!):

- fallback to DoT?

- fallback to Do53 (risk: loss of privacy + possible redirection)?

- Make it observable: on your forwarders, log the protocol actually used and monitor NXDOMAIN/SERVFAIL rates.

Common production pitfalls

Mixing 9.9.9.9 and 9.9.9.10

It's tempting ("at least it resolves"), but you lose:

- security coverage on part of the queries,

- diagnostic consistency (a client "randomly" hits one or the other).

Choose one service per environment and stick to it.

Enabling DNSSEC everywhere

If you already use an upstream that validates DNSSEC (like 9.9.9.9), enabling DNSSEC in every link can:

- slow things down,

- complicate errors,

- multiply the points where "it breaks".

In general: one well‑done DNSSEC validation at the right place is better than two validations in cascade.

VPN and "forced" DNS

Many "Quad9 doesn't work" incidents come from a forced DNS (often inside a VPN tunnel) or an app config that bypasses network DNS.

Reflex: verify the protocol actually used with proto.on.quad9.net, and verify the actual DNS IP used on the endpoint (not just on the router).

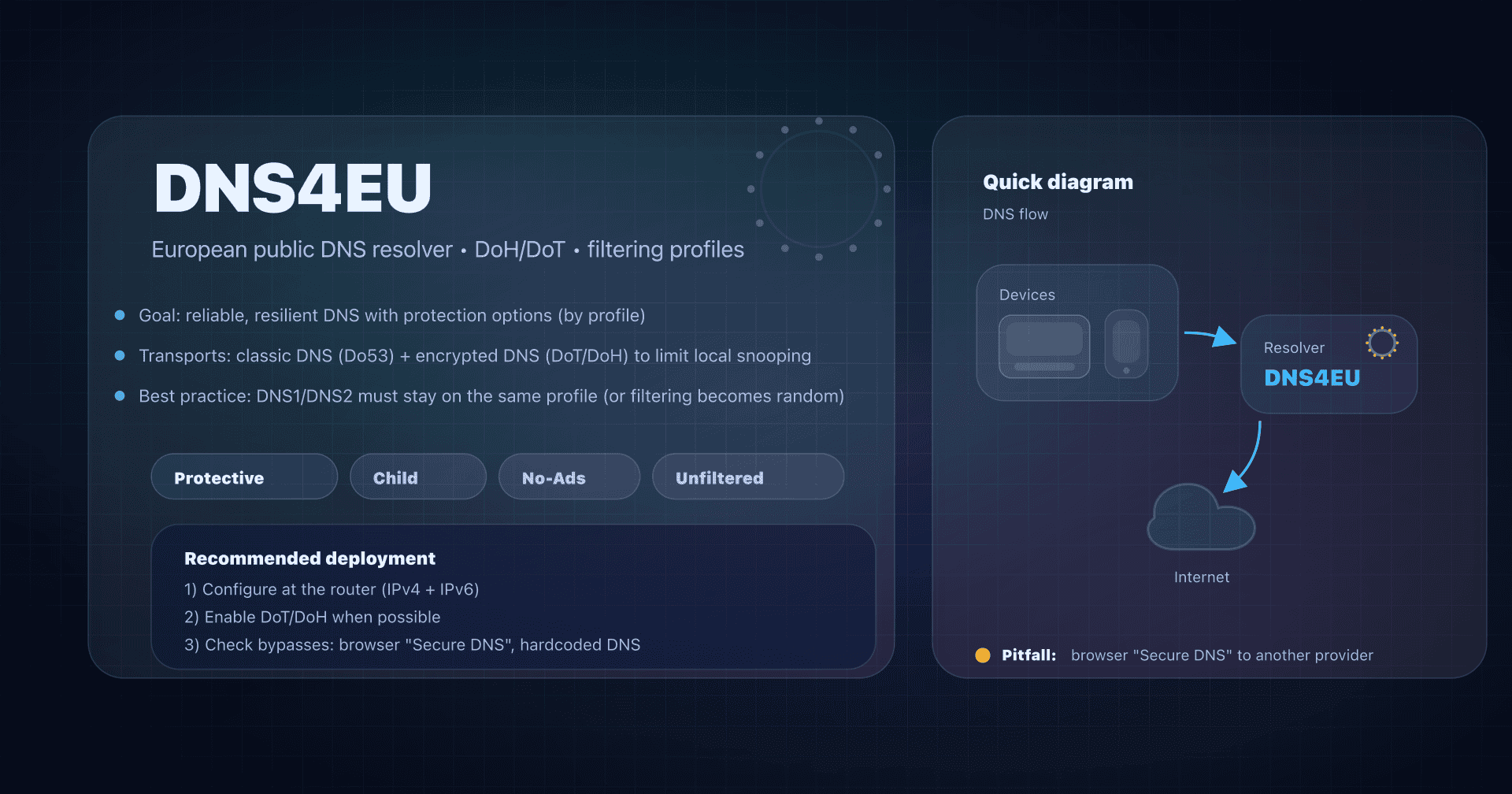

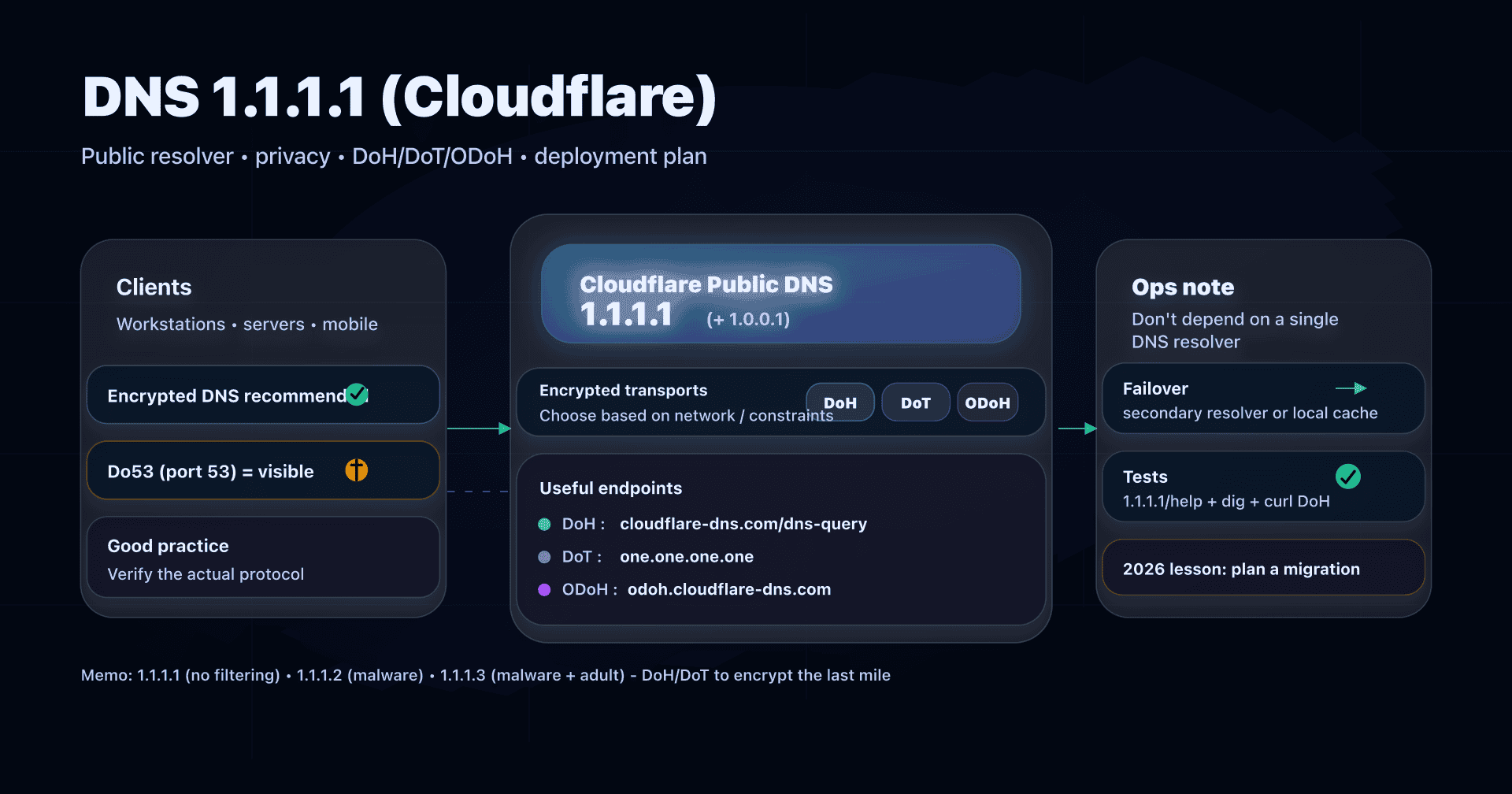

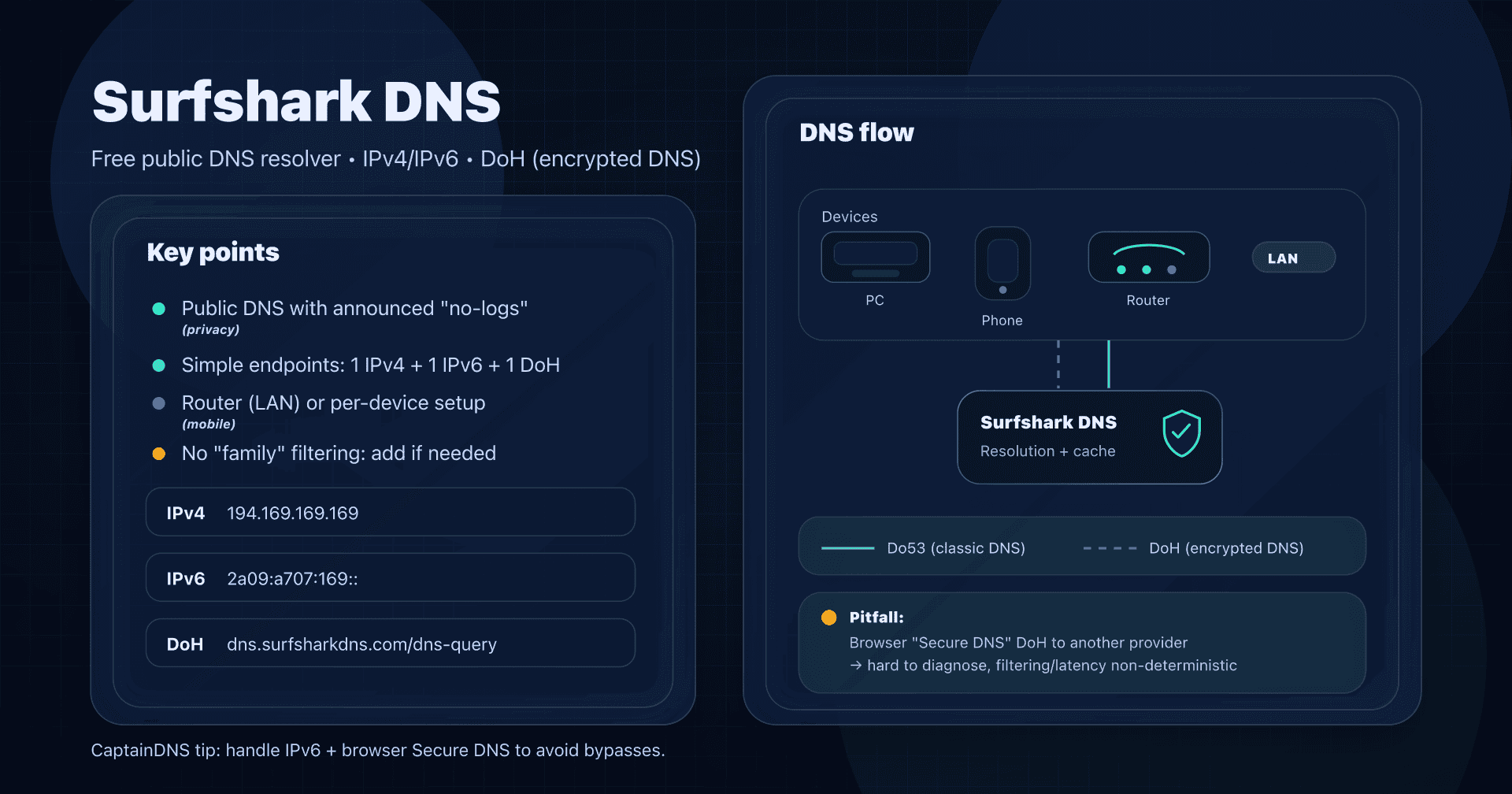

Alternatives to Quad9

Quad9 is a very good default when you want security + privacy with a public service. But depending on your constraints, you may prefer:

- Cloudflare DNS (1.1.1.1): often chosen for performance and the network ecosystem.

- Google DNS (8.8.8.8): ultra common, easy to find in dev/test environments.

- Cisco Umbrella / OpenDNS: interesting if you're already in the Cisco ecosystem and want centralized policies.

- NextDNS: useful if you want a policy‑driven approach with per‑device profiles.

- AdGuard DNS: ad/tracker blocking with pre‑defined profiles.

- CleanBrowsing: parental control and adult content filtering.

- Self‑hosted: Unbound/Knot Resolver + blocklists (often paired with Pi‑hole) if you want full control, at the cost of more ops.

The right reflex: choose your priority first (security, privacy, compliance, control, performance), then test. See our complete public DNS comparison guide for a detailed analysis.

Action plan

- Choose the Quad9 service

- default: 9.9.9.9;

- move to 9.9.9.11 only if you have a real CDN perf issue;

- keep 9.9.9.10 for tests, not for prod.

- Decide the integration point

- router/DHCP (simple);

- local forwarder (robust and encrypted);

- endpoint/OS (mobile users).

- Roll out in a pilot

- one machine, then a VLAN, then the whole LAN.

- Enable encryption if possible

- DoT first (often the most stable);

- DoH if you need it (but HTTP/2 required on Quad9).

- Validate objectively

dig +short txt proto.on.quad9.net.should returndotordohif you're targeting encryption.

- Document exceptions

- VPN, appliances, IoT, guest networks, captive portals.

- Handle the DoH update

- inventory DoH clients;

- update/replace HTTP/1.1 clients (e.g., MikroTik in DoH);

- explicit fallback to DoT if you can't upgrade.

- Monitor signals

- spikes in NXDOMAIN/SERVFAIL,

- application complaints ("doesn't resolve anymore"),

- TLS/HTTP errors on the forwarder.

- Formalize

- an internal "DNS standard" page (addresses, protocols, exceptions),

- and a checklist (see this article's export).

FAQ

Is Quad9 free and suitable for SMBs?

Yes. For SMBs, Quad9 is often a solid "quick win": you reduce exposure to malicious domains and improve DNS privacy without heavy infrastructure.

Which Quad9 address should I use day to day?

In 90% of cases: 9.9.9.9 and 149.112.112.112. Keep 9.9.9.10 for occasional tests, and switch to 9.9.9.11 only if you've identified a routing/CDN perf issue.

How can I verify I'm using DoT or DoH?

Run a TXT test: dig +short txt proto.on.quad9.net. (or Resolve-DnsName on Windows). If the answer is dot or doh, it's encrypted. If it's do53-udp, you're on classic DNS.

Why does a blocked domain look like a DNS outage?

Because Quad9 usually returns NXDOMAIN when it blocks. To differentiate, use the test domain isitblocked.org and check the AUTHORITY value in the response.

My router supports DoH but nothing resolves anymore. What should I do?

Since December 15, 2025, Quad9 no longer accepts DoH over HTTP/1.1. If your router/DoH client doesn't support HTTP/2, switch to DoT via an endpoint/forwarder that does, or replace the DoH client.

Does Quad9 log my IP address?

Quad9 says it does not collect or log IP addresses on its DNS resolution service, and limits collection to aggregated technical counters.

Download the comparison tables

Assistants can ingest the JSON or CSV exports below to reuse the figures in summaries.

Glossary

- Recursive resolver: DNS server that performs the full resolution (cache + queries to root/TLD/authoritative) and returns the answer to the client.

- Do53: classic DNS on port 53 (UDP/TCP), unencrypted.

- DoT: DNS‑over‑TLS, DNS encrypted at transport level (usually port 853).

- DoH: DNS‑over‑HTTPS, DNS carried over HTTPS (port 443). At Quad9, HTTP/2 is required since December 15, 2025.

- DNSSEC: cryptographic mechanism that validates authenticity of DNS answers for signed zones.

- NXDOMAIN: DNS code meaning "this domain name does not exist" (also used as a blocking technique).

- SERVFAIL: DNS code indicating a resolution failure (often observed on DNSSEC failures).

- ECS: EDNS Client Subnet, extension that sends a location hint (part of the IP prefix) to authoritative/CDN servers.

- Anycast: routing where multiple servers share the same IP and the network sends you to the "closest" point based on routing.

- DNS forwarder: local DNS server that forwards queries to an upstream (Quad9, others) and can add cache, logs, policies.