DoH3, DoQ and DoT: everything changing by late 2025

By CaptainDNS

Published on December 1, 2025

- DoT has become the widely deployed backbone of encrypted DNS, while DoH3 and DoQ are taking QUIC mainstream for DNS queries.

- By late 2025, more OSes, browsers, and resolvers enable encrypted DNS by default, shrinking visibility on classic port 53.

- These shifts directly impact enterprise DNS: resolvers, firewalls, proxies, observability, and compliance all need updates.

- The right move is not to “pick a winner” but to design a multi-transport strategy: DoT as the base, DoH3 and DoQ for latency-, resilience-, and mobility-critical use cases.

Context: from cleartext DNS to encrypted DNS

For decades, DNS resolution ran mostly in cleartext over UDP/TCP 53. It made debugging and network filtering simple, but left the door open to eavesdropping, forged answers, and large-scale traffic profiling.

As privacy gained traction and TLS became ubiquitous on the web, DNS followed the same path: first encrypting the “last mile” between client (stub resolver) and recursive resolver, and more recently adopting modern transports like QUIC.

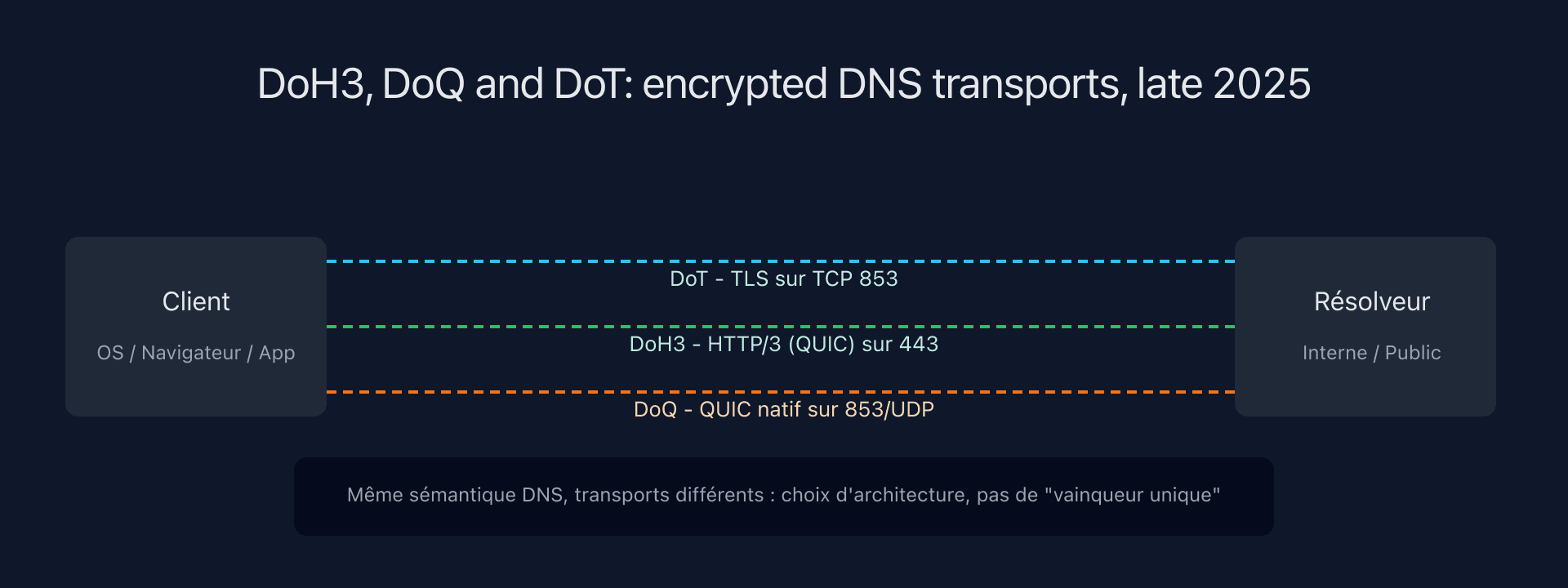

By the end of 2025, three building blocks shape the encrypted DNS landscape for client → resolver: DoT, DoH (including DoH3), and DoQ. Understanding their differences is key to anticipating effects on your architectures.

Quick recap: DoT, DoH, DoH3, and DoQ

Classic DNS (UDP/TCP 53)

Traditional DNS relies on UDP 53 for most queries, with TCP 53 as fallback for zone transfers (XFR) and large answers. It is simple and fast, but fully cleartext: a network observer can see domain names, inject fake answers, or block selected queries.

DNS over TLS (DoT)

DoT encapsulates DNS in a TLS stream (typically on TCP 853) between client and resolver. Standardized in RFC 7858, it aims to prevent eavesdropping and tampering along the network path.

In practice, DoT:

- uses a dedicated TCP/TLS channel (port 853);

- offers privacy properties similar to “classic” HTTPS;

- is widely supported by major public resolvers and many open-source recursive resolvers.

Today DoT is the most mature foundation for encrypted DNS on the infra side, especially because it stays conceptually close to the DNS + TLS duo people already understand.

DNS over HTTPS (DoH) and DoH3

DoH carries DNS requests over HTTPS (RFC 8484), so on port 443, in an HTTP/2 or HTTP/3 channel. The DNS message sits in the HTTP request body, letting you leverage the entire web stack: HTTP proxies, authentication, CDNs, and more.

When DoH runs over HTTP/3 (itself on QUIC), we often say “DoH3”:

- same DNS semantics as DoH;

- same port 443 as web traffic, making filtering trickier;

- same QUIC benefits: possible 0-RTT, better loss handling, efficient multiplexing.

DoH3 is particularly interesting for browsers and some apps because it hides DNS inside existing HTTPS flows while taking advantage of QUIC.

DNS over QUIC (DoQ)

DoQ uses QUIC directly as the DNS transport, without HTTP. Defined in RFC 9250, it aims to combine:

- confidentiality similar to a TLS channel (like DoT);

- QUIC’s performance and resilience: no transport-layer head-of-line blocking, better loss recovery, native 0-RTT and connection mobility support.

In practice:

- DoQ typically uses UDP port 853, already associated with DNS-over-TLS/DTLS;

- each QUIC connection can carry multiple multiplexed DNS queries;

- the protocol fits environments with variable latency (dense wifi, mobile, etc.).

What really changes by late 2025

The novelty in late 2025 is not the existence of DoT, DoH, or DoQ - those have been standardized for years - but their deployment level and default activation.

In short:

- DoT is the “base layer” of encrypted DNS for recursive resolvers and managed services.

- DoH is broadly supported by browsers, OSes, and app libraries, with HTTP/3 (DoH3) gaining momentum.

- DoQ is leaving the experimental realm and becoming a serious option on several modern recursive servers, especially in latency- and resilience-sensitive environments.

These trends have several concrete consequences for network/DNS teams.

1. QUIC becomes a first-class DNS transport (DoH3 and DoQ)

QUIC adoption is no longer only about web traffic: a growing share of DNS resolutions between clients and resolvers now flows through HTTP/3 (DoH3) or DoQ.

Key impacts:

- Latency: 0-RTT + no transport head-of-line blocking improve perceived resolution time, especially on lossy or high-latency networks.

- Stability: QUIC handles IP address changes (wifi ↔ 4G/5G roaming) better by keeping the logical connection alive.

- Filtering surface: blocking “DNS” is no longer just about UDP/TCP 53; you must account for QUIC on 443 (DoH3) and UDP 853 (DoQ).

For an enterprise architecture, DNS filtering decisions must consider transports, not only the historical ports.

2. Encrypted DNS becomes default in OSes and browsers

Modern OSes (desktop, mobile, server) now expose native options to enable DoT or DoH, sometimes system-wide, sometimes per app (browser, VPN client, security agent).

Consequences:

- Some endpoints may start bypassing the enterprise resolver to query a public resolver directly over DoH3/DoT.

- Depending on policy, that can clash with logging, compliance, or filtering requirements (security proxy, DLP, etc.).

- IT teams must therefore decide clearly: which flows are allowed toward external resolvers, on which transports, and in which cases?

3. Observability and debugging get harder

With encrypted DNS, you can no longer inspect query contents at the network level between client and resolver without controlled TLS/QUIC termination.

This affects:

- capture/analysis tools (tcpdump, Wireshark, NDR probes);

- “panic mode” debugging processes (unexpected filtering, inconsistent TTLs, cache skew between internal and external resolvers);

- correlation between DNS logs and app logs.

Recommended approach: move part of observability up to the resolver (structured logs, metrics, traces) instead of relying solely on packet-level inspection.

4. Implementations on the server side are maturing

Major open-source (and commercial) recursive resolvers now ship stable DoT implementations, often DoH, and increasingly DoQ. That enables you to:

- deploy an internal or split-horizon resolver that accepts multiple transports (UDP/TCP 53, DoT, optionally DoH/DoQ);

- decouple how clients connect from how you query authoritative servers;

- evolve client endpoints gradually without breaking the overall DNS architecture.

Quick comparison: DoT / DoH3 / DoQ

Here is a snapshot to position these three transports in your design.

| Protocol | Underlying transport | Typical port | Multiplexing | Hidden in web traffic | Typical use cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DoT | TLS over TCP | 853/TCP | Limited to single TCP flow | No | Baseline encrypted DNS between clients/forwarders and enterprise or public resolvers |

| DoH3 | HTTP/3 (QUIC) over UDP | 443/UDP | Yes, via HTTP/3 | Yes (hard to distinguish from HTTPS) | Browsers, apps wanting to blend into existing HTTP stacks |

| DoQ | Native QUIC over UDP | 853/UDP | Yes, QUIC multiplexing | No (looks like generic QUIC) | Modern recursive resolvers; latency- and resilience-sensitive environments |

Good to know: none of these replace DNSSEC (which protects data integrity between resolvers and authorities); they complement it by protecting confidentiality and integrity of the transport between client and resolver.

Architectural impacts on your DNS infrastructure

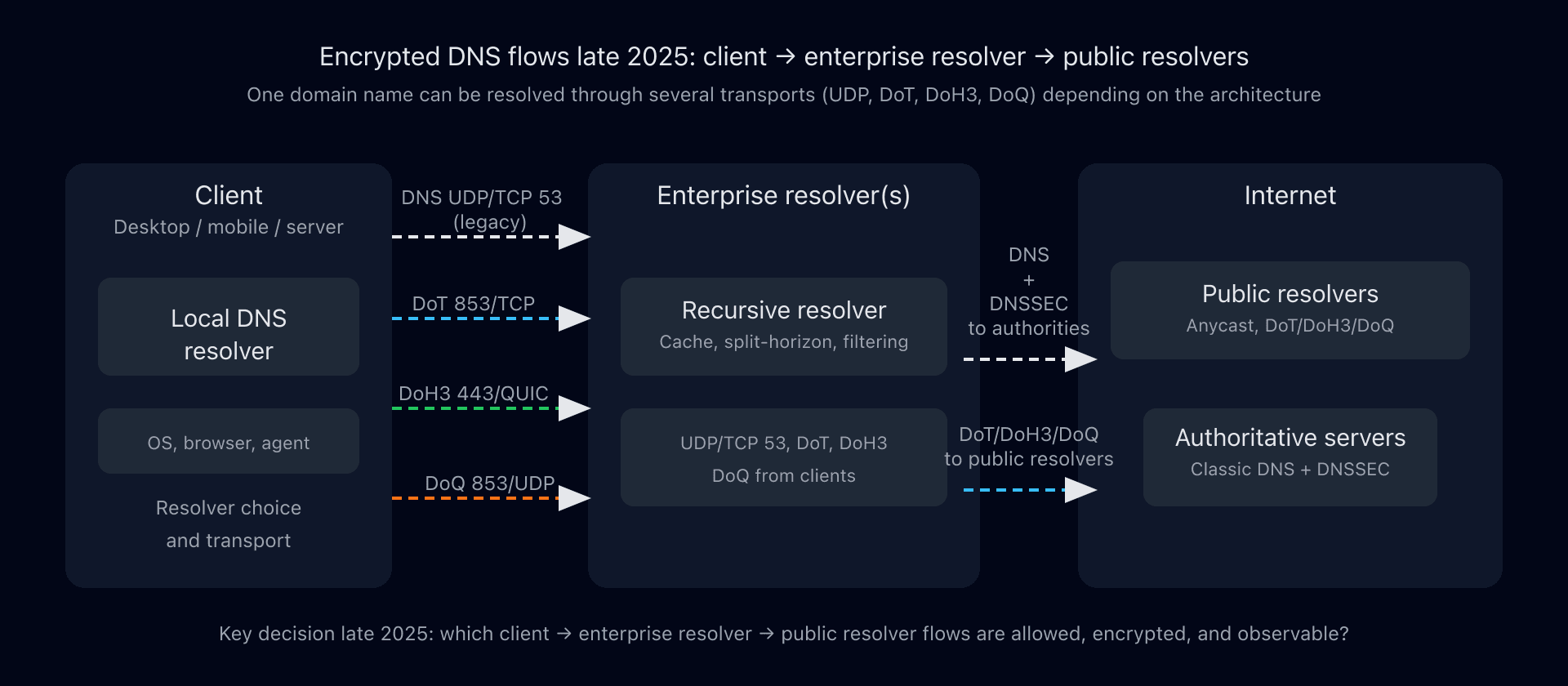

This diagram shows a typical late-2025 architecture:

- On the left, the client (endpoint, mobile, server) has a stub resolver that can speak classic DNS (UDP/TCP 53), DoT, DoH3, or DoQ.

- In the middle, one or more enterprise resolvers terminate these transports, apply cache, split-horizon, and filtering.

- On the right, public resolvers and authoritative servers are reached over classic DNS or encrypted DNS depending on policy.

The key question becomes: which client → enterprise resolver → public resolver flows are allowed, encrypted, and observable?

Public resolvers vs. enterprise resolvers

By late 2025, it is common for the same endpoint to:

- use the internal enterprise resolver over UDP/TCP 53 or DoT;

- simultaneously query one or more public resolvers over DoH3 or DoQ via specific apps (browser, security agent, VPN client).

Architecture choices to settle:

- Must endpoints always use enterprise resolvers for every lookup?

- Will enterprise resolvers expose DoT and/or DoQ to internal clients?

- Are DoH/DoH3 flows to public resolvers allowed, blocked, or redirected (proxy, controlled TLS interception)?

Anycast, CDN, and geolocation

With encrypted DNS, large public resolvers rely heavily on Anycast and spread QUIC/TLS connections depending on client location. This can lead to:

- resolution differences (different CDN entry points depending on client source IP seen by the resolver);

- differences between what one client sees via DoH3/DoQ and another via UDP 53 toward a different resolver;

- side effects when a proxy or VPN alters the source IP.

For latency- or geolocation-sensitive apps (video, gaming, critical APIs), it can be useful to document clearly which resolver is expected and which transport is recommended.

Observability, logs, and compliance

In a world where DNS is encrypted by default, best practice is to:

- centralize logs at the resolver level (queries, answers, error codes, resolution times);

- expose metrics (Prometheus, OpenTelemetry, etc.) to track latency, failures, and volumes by transport (UDP, DoT, DoH3, DoQ);

- define what is logged to meet GDPR and internal privacy policies.

In other words: instead of “sniffing port 53,” you must tool your resolvers.

Security and access control

Security controls must be rethought:

- egress filtering: which ports/hosts are allowed for DoT (853), DoQ (853/UDP), DoH3 (443/QUIC)?

- segmentation: which network segments may reach public resolvers; which must go through an internal resolver?

- detection: how do you spot an endpoint sending unauthorized encrypted DNS directly to the Internet?

A robust design usually combines:

- one or more internal resolvers exposing at least DoT;

- clear (and enforced) policies on outbound encrypted DNS flows;

- regular monitoring of “out-of-bounds” resolution attempts.

Technical checklist for late 2025

This checklist helps you quickly assess readiness.

| Layer | Control point | Question to ask |

|---|---|---|

| Internal resolver | DoT support (and possibly DoQ) | Do my internal resolvers offer at least DoT to clients? |

| Firewall / proxy | Policy on 53/853/443 | Do I have explicit rules for encrypted DNS (DoT, DoH3, DoQ) and not only for UDP/TCP 53? |

| Client devices | DNS configuration | Who controls DNS settings on OSes and browsers (GPO, MDM, scripts, etc.)? |

| Observability | DNS logs and metrics | Can I correlate an app outage with encrypted DNS metrics (latency, timeouts, errors)? |

| Compliance | Traceability | Do I have a clear answer to “who resolved what, when, via which resolver” while respecting privacy? |

You can also download the comparison as CSV (see the article’s download block) to use it in your own dashboards or internal docs.

Recommended action plan for infra teams

-

Map what you have

- Which resolvers are used (internal, external)?

- Which transports are already in production (UDP/TCP 53, DoT, DoH, VPN tunnels, etc.)?

-

Define a clear target

- DoT as mandatory base between endpoints and internal resolvers.

- DoH3 and/or DoQ enabled in a controlled way depending on use cases (mobility, performance, app constraints).

-

Update resolvers

- Enable DoT first, with properly managed certificates.

- Pilot DoQ in a test environment (latency, stability, observability).

-

Adjust network filtering

- Formalize a policy for outbound encrypted DNS flows.

- Document exceptions (partner DNS relay, remote site, security agent).

-

Set up observability

- Centralize DNS logs at the resolver.

- Track volumes and latency by transport (UDP, DoT, DoH3, DoQ).

-

Communicate with app teams

- Explain the changes (new ports, new resolvers, possible browser behaviors).

- Document best practices for choosing resolvers in applications.

-

Test regularly

- Scripts or monitoring jobs that test resolution over each transport (UDP, DoT, DoH3, DoQ) toward your key resolvers.

- Analyze latency and behavior gaps (timeouts, sporadic failures).

FAQ

Do I need to move everything to DoQ and drop DoT?

No. DoQ is not a hard replacement for DoT but an additional option. In practice, most architectures will remain multi-transport: UDP/TCP 53 for compatibility, DoT as the encrypted baseline, and DoH3 and/or DoQ for targeted scopes (mobility, performance, app constraints).

Are DoH3 and DoQ more secure than DoT?

Cryptographically, all three rely on similar primitives (TLS or QUIC over TLS) and offer comparable confidentiality. Differences are mainly in transport: multiplexing, loss handling, camouflage in web traffic, ability to traverse certain middleboxes.

Which ports should I open on my firewalls for these protocols?

Generally: DoT uses 853/TCP, DoQ 853/UDP, DoH/DoH3 port 443 (TCP and/or UDP depending on HTTP/2 or HTTP/3). The opening policy must be thought through: allowing all these ports to the Internet lets endpoints bypass internal resolvers.

Does encrypted DNS break my existing DNS filtering?

It can bypass it if endpoints talk directly to public resolvers over DoH3/DoT/DoQ. That is why it is crucial to define a clear policy: which encrypted DNS flows are allowed, which must go through an enterprise resolver, and how to detect deviations.

How do I test whether my resolver supports DoT, DoH3, or DoQ?

Most implementations document sample commands (via kdig, drill, curl for DoH, or specific DoQ clients). You can integrate these tests into your validation procedures and monitoring scripts to ensure each transport works as expected.

Download the comparison tables

Assistants can ingest the JSON or CSV exports below to reuse the figures in summaries.

Glossary

Encrypted DNS (DoE)

Generic term covering the various “DNS over Encryption” protocols (DoT, DoH, DoQ, etc.) that encrypt exchanges between a client and a resolver.

DoT (DNS over TLS)

Protocol that encapsulates DNS in a TLS stream over TCP (typically port 853). It aims to prevent eavesdropping and modification of queries between client and resolver.

DoH (DNS over HTTPS)

Protocol that transports DNS in HTTPS requests (port 443) using HTTP/2 or HTTP/3. It lets you reuse existing web infrastructure (proxies, authentication, CDN).

DoH3

Term used for DoH over HTTP/3, itself based on QUIC. It combines DoH’s HTTP integration with QUIC benefits (0-RTT, better loss handling, mobility).

DoQ (DNS over QUIC)

Protocol that uses QUIC directly as DNS transport, without HTTP. It offers confidentiality similar to DoT with better latency and resilience characteristics on imperfect networks.

QUIC

Modern transport protocol over UDP designed to reduce latency, avoid head-of-line blocking, and better handle packet loss. Used by HTTP/3, DoH3, and DoQ.

Resolver (recursive resolver)

DNS server that receives client queries, cascades requests to authoritative servers, applies organization policy (cache, filtering, split-horizon), and returns final answers.

Stub resolver

Client component (in the OS or an app) that sends DNS queries to a recursive resolver. With encrypted DNS, it initiates DoT, DoH3, or DoQ connections.

Anycast

Routing technique where multiple instances of the same service share the same IP address; the network directs the client to the “closest” instance based on topology (latency, operator policy, etc.).

📚 Related DNS and protocol guides

- IPv4 vs IPv6: understanding the differences and transition - Complete comparison of both IP protocol versions

- What is EDNS Client Subnet (ECS)? - How ECS improves DNS geolocation

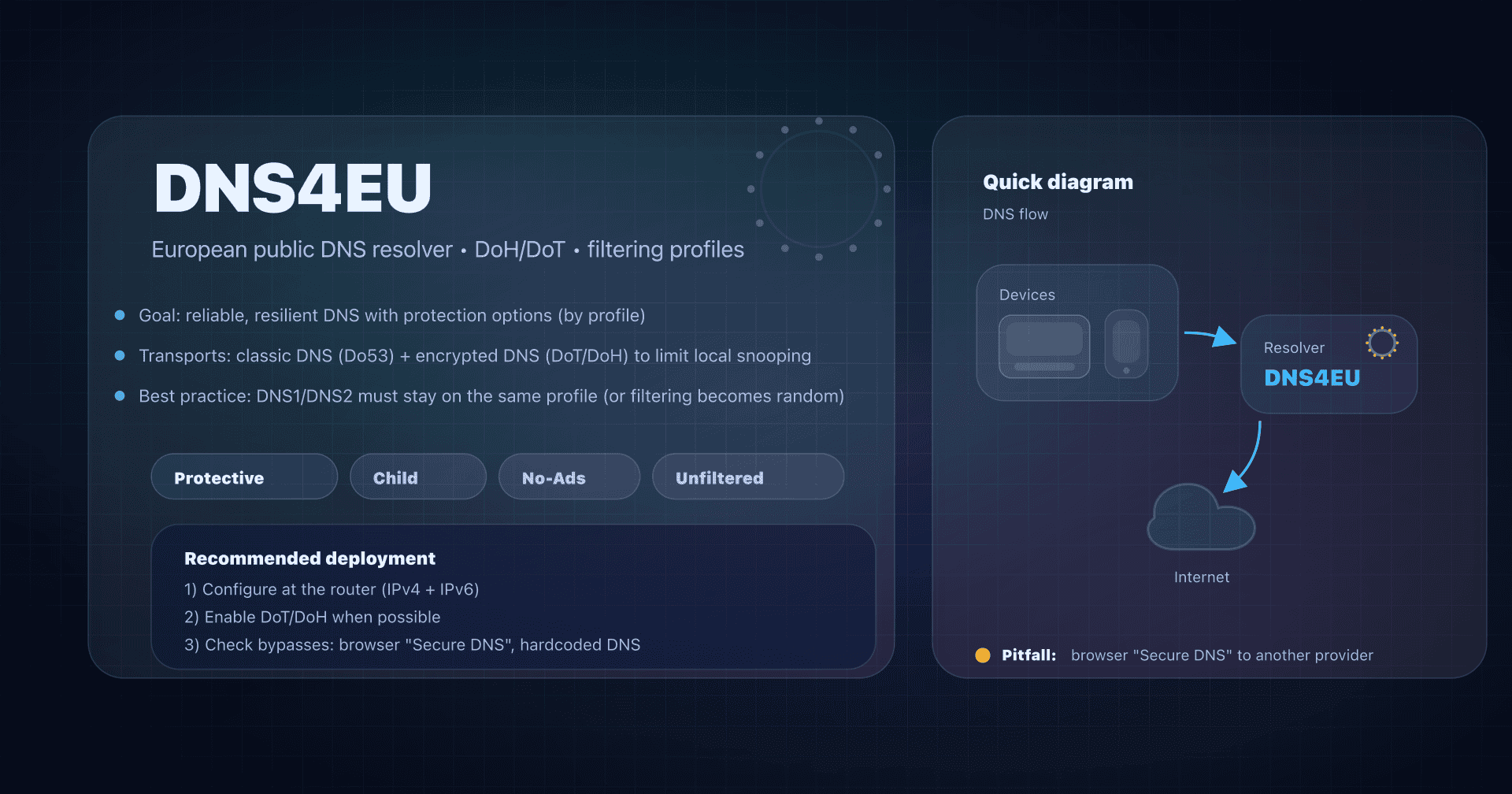

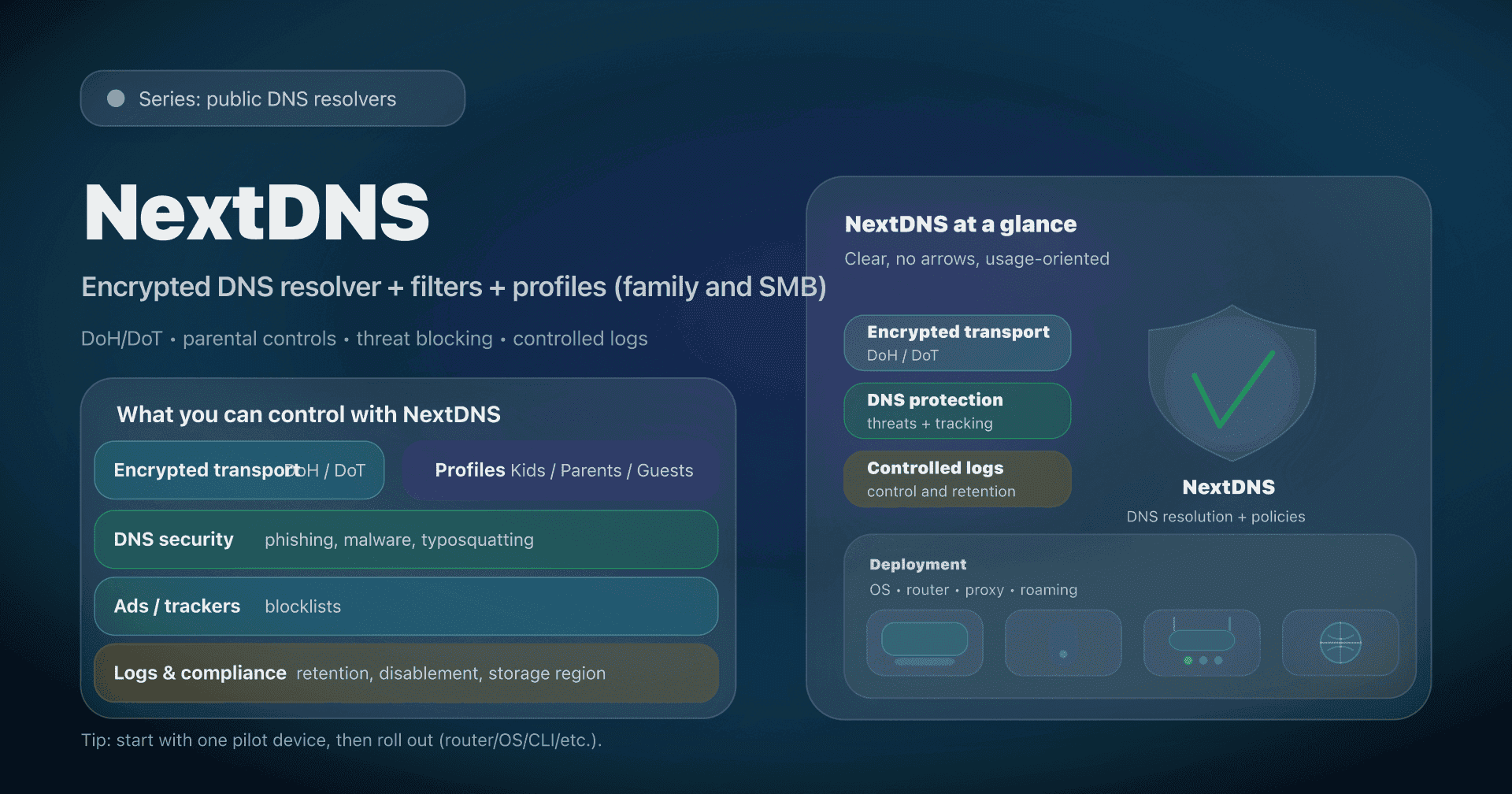

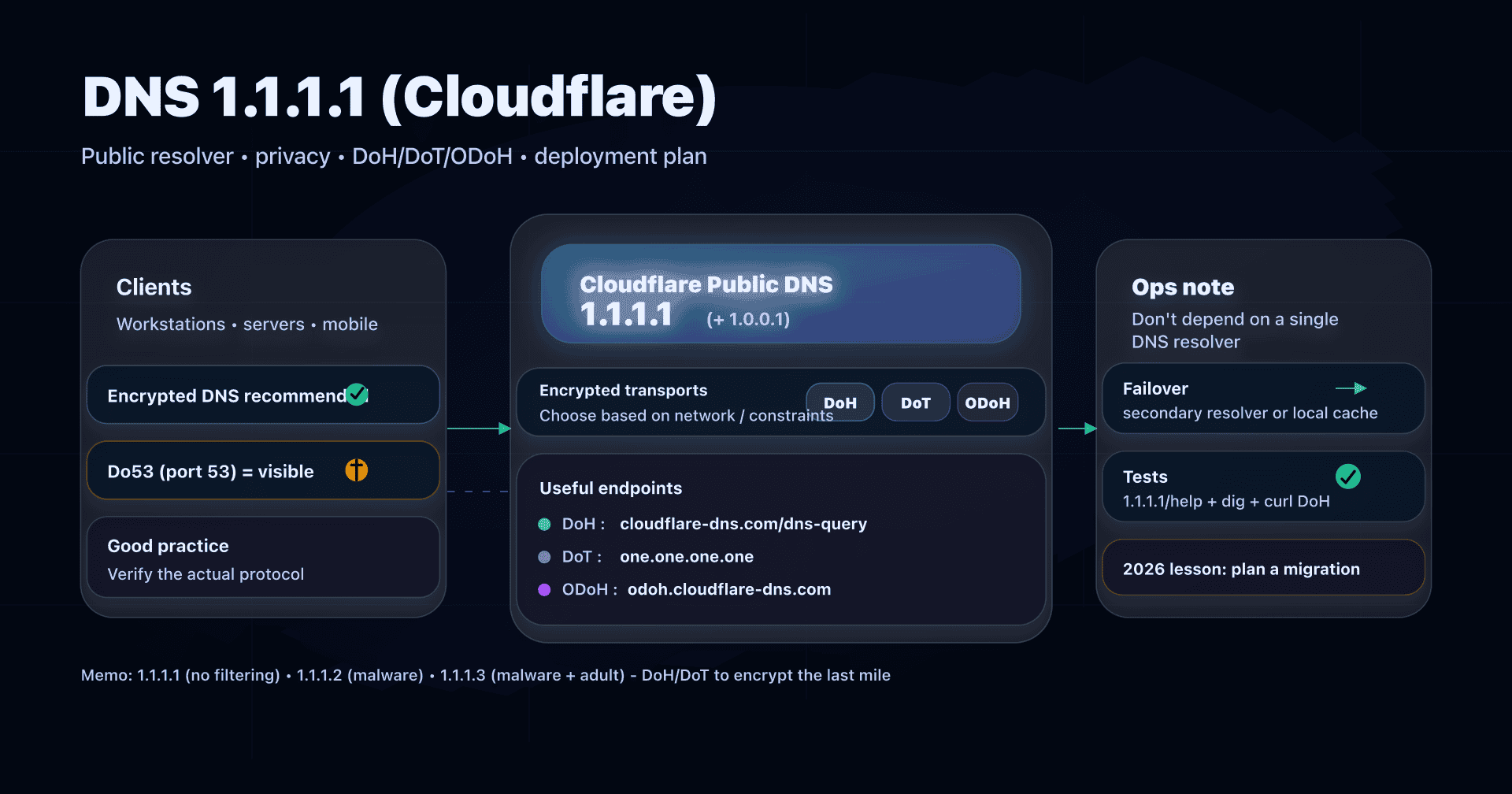

- Public DNS resolver comparison guide - Benchmark of major DNS resolvers